My car is limping, Dolores Haze,

And the last long lap is the hardest,

And I shall be dumped where the weed decays,

And the rest is rust and stardust.

Directly before the closing line we must twist ‘decays’ to rhyme ‘Haze’. Our lip turns up and a snarl is begun. The ignition pressed, we rev the two ‘r’ sounds in ‘rest’ and ‘rust’ with rising gusto. We enter the third, final ‘r’ we will make violence of it, then find that ‘star’ permits no revving whatever. Our snarl collapses and then immediately, with no time to regather ourselves, we are forced to produce, and can only do so weakly, the closing syllable: ‘dust’.

In a car singalong you pause the music just as your friend tries the big note, and leave himi for one cruel phoneme so desperately abandoned. He is alone, and exposed, and all the self-consciousness he’d suspended comes crashing back down on him in a single, awful instant.

Speaking the above verse is a character of immense and elusive bravado whose underlying terror we always suspect but can never ascertain surely. That it is glimpsed in this poem for the briefest unit our language has, one syllable, that ‘dust’, is an extraordinary feat of precision.

‘Last long lap’ in the second line are three libilant syllables of contracting length, which is just like – and consider the fineness of vowel management involved here – their source’s title: Lo-lee-ta.

Almost no one’s first Nabokov book is not Lolita but Lolita can deter readers. They find the prose or the plot too sickly. Or they just think they have done the main one, and while it was impressive, they don’t fancy another.

It took me a while to revisit him after first reading Lolita. Partly I wanted to hate it because it was an ex’s favourite book, but also I agreed with James Wood calling the prose ‘overdeveloped’ and found the story quite gross. Most of all, though, I wanted instruction from my reading and Nabokov refused to give it. He insisted on “games” as opposed to “lessons”.

I only enjoyed the stanza we began with when I found it isolated from the rest of the book. There was a YouTube clip of Nabokov reading poetry. With the words in his mouth you could hear how surprisingly he relished and played with language and discern the “lolling and loafing which allowed first of all the formation of Homo poeticus”. Nabokov said Shakespeare’s “verbal poetic texture is the greatest the world has ever known”, but Amis was within his rights to call Nabokov himself “the nearest thing to pure sensual pleasure that prose can offer”.

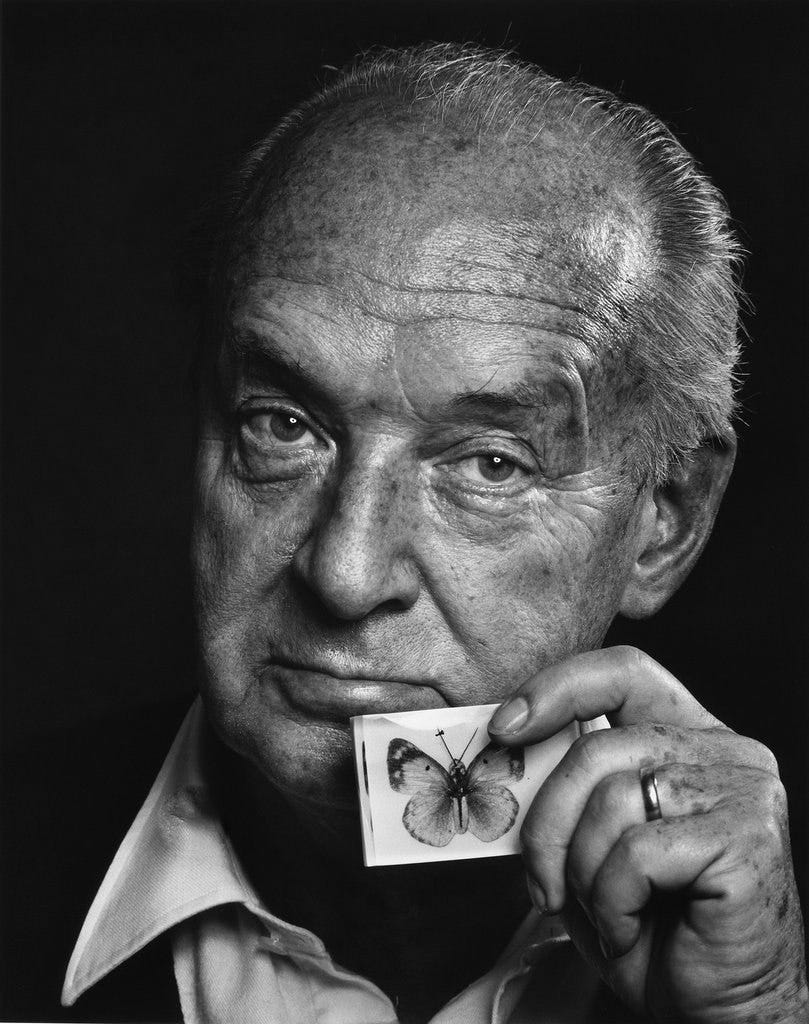

After that YouTube clip I tried the other books. They, too, make the sensual case by example. Pale Fire holds a supremely intense midnight of “nonutilitarian delights” at its mystery’s completion. The hobbyist amusements of chess puzzles and lepidoptery are described so brilliantly in Speak, Memory that the entirely oblivious reader can participate in them. Finally, of course, the pleasures and language and vision are exquisite throughout: drifting snowflakes as “shapeless and slow”, Colorado as a “montane zone” (think how superior to “mountainous region”), and the province of Zembla as “romance, remoteness, sealskin-lined scarlet skies, the darkening dunes of a fabulous kingdom”.

Maybe finding Lolita too thick is indeed, as Nabokov himself said, “An example of British cant – tabooing a writer because of his morals.” But your reaction can’t always be helped, and I was glad the other works made easier basking, and coaxed you more gently to their pleasures. With them you drift along the spectrum of King, Queen, Knave characters from Dreyer to Franz: less “the morose temper of genius” and more “full of ruddy life”, less the student and more the “vigorous though unorthodox skier”.

The laughs are readier outside Lolita. The villains are less sinister, the ‘prey’ only bemused, and the non-fiction mocks its author.

I was less the keeper of a soccer goal than the keeper of a secret. As with folded arms I leant my back against the left goalpost, I enjoyed the luxury of closing my eyes, and thus I would listen to my heart knocking and feel the blind drizzle on my face and hear, in the distance, the broken sounds of the game, and think of myself as of a fabulous exotic being in an English footballer’s disguise, composing verse in a tongue nobody understood about a remote country nobody knew. Small wonder I was not very popular with my team-mates.

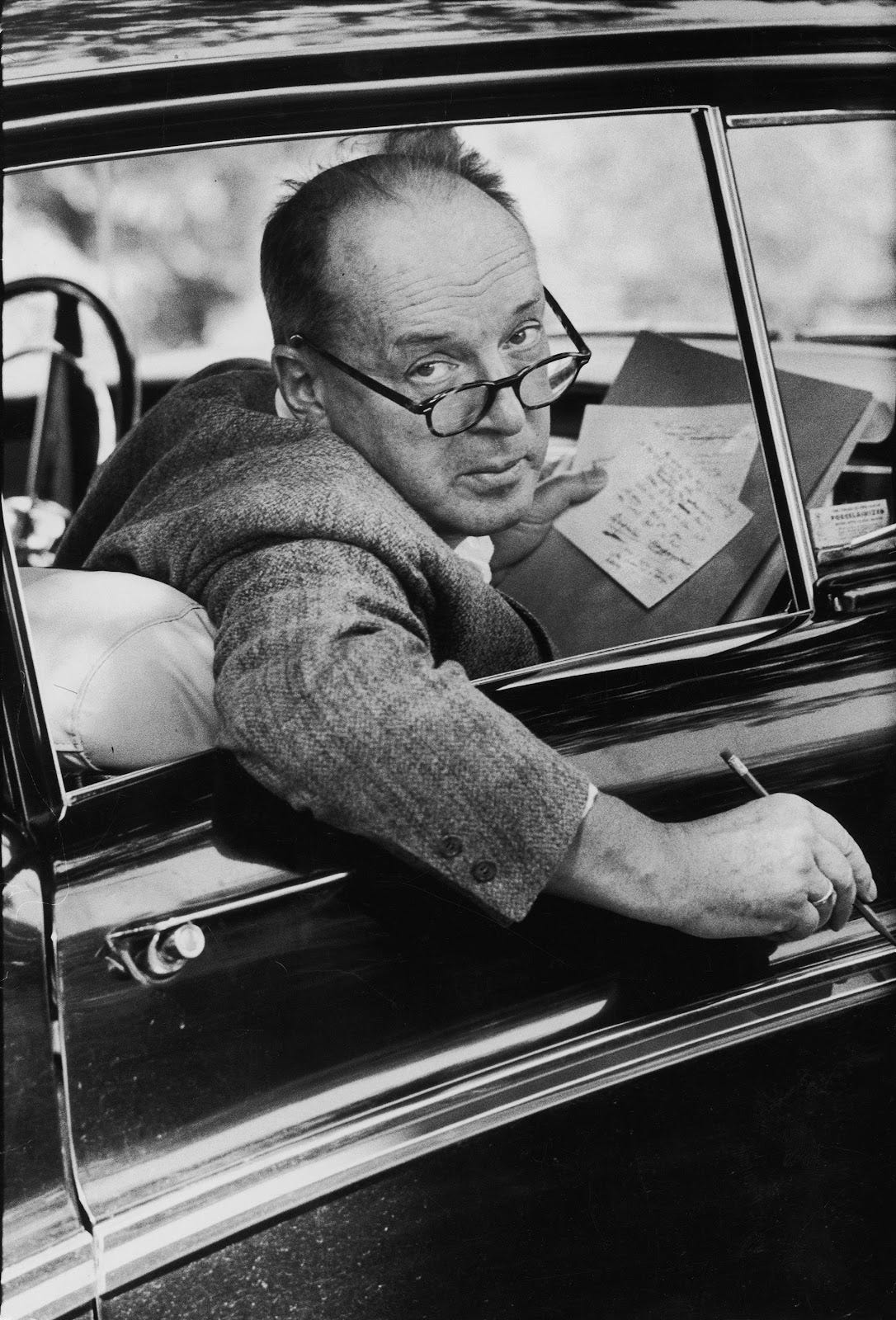

The fun lies in these flights and crashes of self-regard. He thought himself too wretched a speaker to be interviewed without pre-written answers. Yet he reassured prospective interviewers that by “little tricks of hesitation and so forth… the spectator will not be aware I am reading”. In fact, footage shows his undetectable tricks to mean staring very obviously at his cards. Still his supposedly ‘spontaneous’ answer is flawlessly baroque, opening “Pleasure and agony while composing the book in my mind; harrowing irritation when struggling with my tools and viscera – the pencil that needs resharpening, the card that has to be rewritten, the bladder that has to be drained…”

It goes on for 162 words. Asked, however, if he could say how important his wife has been to him and his work, he has but four: “No, I could not.”

Family love is absent from Lolita and touched only obliquely in most of other work. Shade’s (Pale Fire) tribute to his wife is kept between scornful annotations as “embarrassing intimacies”. A Nabokovish couple (King, Queen, Knave) is spotted in playing chess “over the bright oasis of the happy table”, then dancing, with him “contemptuous of everything on earth but her… looking at her with pride”, but they are peripheral and appear only in “fleeting glimpses”.

Thankfully the theme does get full voice somewhere. Speak, Memory’s ravishing fifteenth chapter, recounting “the years of our boy’s infancy” is among the most enchanting and encouraging I’ve ever known. Vladimir and Véra spot a train around the corner of their son’s path:

you and I saw something that we did not immediately point out to our child, so as to enjoy in full the blissful shock, the enchantment and glee he would experience on discovering ahead the ungenuinely gigantic, the unrealistically real prototype of the various toy vessels he had doddled about in his bath.

The sole issue of Nabokovian life advice, then: “never, never say, ‘Hurry up,’ to a child.” The supreme existence, he knows, is the imaginative one of “the immature and the immortal”, lived rapt to detail.

But we might ask how he came to this wisdom. The answer, I think, is illustratively threefold. At first there was the happy example of his mother drawing his attention to “loved things” – larks, lightning, leaves. Then a clever tutor had him detail unexamined familiarities like his front door from memory. Finally, though, he reads from university of his childhood Russia being laid to waste, and mourns “the things I would not have omitted to note and treasure, had I suspected before that my life was to veer in such a violent way.”

Twentieth-century tragedy is barely visible in Lolita and is never more than faint. But Nabokov fled Russia from the Bolsheviks, fled Berlin from early-Nazism, and fled Paris from the Wehrmacht. He lost his father to an assassin and his brother to Neuengamme. Shade glancingly opines that “a dictator needs a secret police, and that is the end of the world.” Pnin (Pnin) won’t celebrate his new birthday because America’s Georgian calendar moved its date by 13 days.

As family love is the plainest-told joy, family woe is the most uncomplicated ill. Shade’s daughter is ugly from birth and comes to know it with horrible inevitability. As Joan comforts Pnin after his hopes with the woman he loves die, Joan’s husband gets home, and Pnin sees her trying to smile some happy news across without him seeing.

I don’t know why, but causeless, internal melancholies are placed in Nabokov’s worst hearts. History’s “freakish tides” afflict characters impersonally and family pain befalls sympathetic ones. But that “stardust” was Humbert Humbert’s and these next lines are Kinbote’s (Pale Fire). Both are monsters.

Of the not very many ways known of shedding one’s body, falling, falling, falling is the supreme method, but you have to select your sill or ledge very carefully so as not to hurt yourself or others. … the sweet urge to close one’s eyes and surrender utterly unto the perfect safety of wooed death. Ecstatically one forefeels the vastness of the Divine Embrace enfolding one’s liberated spirit, the warm bath of physical dissolution, the universal unknown engulfing the minuscule unknown that had been the only real part of one’s temporary personality.

Why do only monsters have such thoughts? Probably it is philistine to ask knowledge of this corpus. A book’s world is a new one, with no bearing on ours. Good readers bring only imagination, memory, a dictionary and artistic sense. They “soar into the ravishing realm of inutile imagination”. Again, they read for, “games, not lessons.”

The trouble is that – after three ironic refractions, anyway, in a mock afterword’s mock description of mock poetry – there can be games like this:

…a game that was surely silly but seems less silly now when it is seen to fall into the pattern of predicted loss, of pathetic attempts to retain the doomed, the departing, the lovely dying things of a life that was trying, rather desperately, to think of itself in terms of future retrospection.

GM

Afterbirth

Here is that clip of the poetry reading. Wanted, Wanted, the poem quoted at our start, begins at 50:44, but the whole thing is wonderful.

Thanks for reading this. I hope it is worthy. Criticism collections are often divided into a section for the topics or authors someone just happened to write about and the one for those that were really the great loves. This is my first submission to the latter. You feel you have to do those ones before you die. Oddly, you also feel you only have one crack at them. Your writing defines your feeling so if you write incorrectly you lose your feelings. My feelings about Nabokov are very dear to me so hopefully I haven’t just lost them! But only years will judge that.

I enjoyed your article very much. I once possessed (and read) most of Nabokov’s works - oh, hundreds of years ago - but now I have on my shelves only ‘Speak Memory’, his wonderful book on Gogol, ‘Lectures on Literature’, his translation of Lermontov, and that brief late novel ‘Transparent Things' for which I retain an affection the reasons for which I have never understood. What made me fall out with his novels was, I think, the snobbishness, and the games he played with, and on, the reader. I have come to wonder whether Thomas Mann’s judgement on Ernst Jünger (‘a cold dandy’) may not be applicable also to Nabokov.