Tuesday will be seventy-five years since the death of George Orwell. Quite minor a date, but so massive a figure – patron saint of English decency, balletic navigator of twentieth-century tides, nominative source of a new word for ‘bad’ – that we can expect a broad flurry of pieces. All will draw on his Essays, which are as close as this nation comes to required reading, but few will mention his early novel, Keep The Aspidistra Flying.

The last essay, in the Penguin collection anyway, is a reflection on Mohandas Gandhi. Orwell, writing in 1949 for a Western audience, spends a fair while describing Gandhi’s spiritual practice. Oddly though, when I read it, Gandhi’s ideas were in many ways more familiar than Orwell’s. I was passing my covid lockdowns fasting, meditating, and sitting on the floor to stare at candles.

Oddly, the first decisively damaging blow Orwell lands is that Gandhi wouldn’t season his food. “No spices or condiments, even of a vegetable kind, since food should be taken not for its own sake.” It is an almost ridiculously trivial observation, but that’s why it’s so sticky. How, we ask, could it possibly enlarge your moral contribution to decide not to salt your eggs or pepper your pasta (or cheese your chips)? It’s a hard charge to answer. And so is the one it summons: why should we trust the judgement of a man who, spearheading what he believes is an important moral cause, devotes energy to shunning paprika? Then, having scored on the small plates, Orwell moves to a bigger target.

A very common aim in spiritual thinking is transcending the self in order to join a universal whole and be equally attached to all existence. At the time of reading I had been to a late-2010s university, so had evolved a fairly robust suspicion of certain spiritual practitioners and practices. It would have been hard not to notice that certain campus advocates had more interest in substituting their self for the universe than the universe for their self, or that pansexuality mostly involved attraction to talking about oneself. But the older arguments for transcendence still seemed quite agreeable, and I certainly had no beef with universal love.

I had heard the complaint of Christopher Hitchens that Christianity’s command to love one’s neighbour as one’s own is immoral because impossible, and had found its source in an earlier Orwell essay : religion was “strewn with psychological impossibilities… It was not that one did not want to possess the right qualities or feel the correct emotions, but that one could not. The good and the possible never seemed to coincide.”

But the argument in the Gandhi essay was different. Orwell didn’t say universal love was impossible. He said it was undesirable. He articulated, thrillingly, what universal love must cost us. This long quote takes 80 seconds to read, apologies:

And finally – this is the cardinal point – for the seeker after goodness there must be no close friendships and no exclusive loves whatever. Close friendships, Gandhi says, are dangerous … if one is to love God, or to love humanity as a whole, one cannot give one’s preference to any individual person. This again is true, and it marks the point at which the humanistic and the religious attitudes cease to be reconcilable. To an ordinary human being, love means nothing if it does not mean loving some people more than others.

…

The essence of being human is that one does not seek perfection, that one is sometimes willing to commit sins for the sake of loyalty, that one does not push asceticism to the point where it makes friendly intercourse impossible, and that one is prepared in the end to be defeated and broken up by life, which is the inevitable price of fastening one’s love upon other human individuals. No doubt alcohol, tobacco and so forth are things that a saint must avoid, but sainthood is also a thing that human beings must avoid.

…

In this yogi-ridden age, it is too readily assumed that ‘non-attachment’ is not only better than a full acceptance of earthly life, but that the ordinary man only rejects it because it is too difficult: in other words, that the average human being is a failed saint. It is doubtful whether this is true. Many people genuinely do not wish to be saints, and it is probable that some who achieve or aspire to sainthood have never felt much temptation to be human beings. If one could follow it to its psychological roots, one would, I believe, find that the main motive for ‘non-attachment’ is a desire to escape from the pain of living, and above all from love, which, sexual or non-sexual, is hard work.

That a wonderful image, of an unsaintly life of close friendly loves, emerges in the essay as a negative reflection of Gandhi’s ideal. It is drawn in full colour in Keep The Aspidistra Flying.

We can save time, all of us having studied Richard Curtis so intensely lately, by saying that the plot is Notting Hill: downtrodden bookseller ends up with a girl. But where some (not me!) would say Notting Hill lacks hardship, no one could miss it Aspidistra.

Gordon Comstock is ugly, poor and sickly, and so is the world he lives in. His life is “dingy and depressing.” Years slip by, “always the same. The lonely room, the womanless bed; dust, cigarette ash, the aspidistra leaves.” He is not loved, seen or known. It is “day after day with never an intelligent person to talk to; night after night back to your godless room, always alone.”

He is not even manage a vivid unhappiness, so thoroughly does he fail ever to be “fully alive”. The Comstocks are “listless, gutless, unsuccessful… grey, shabby joyless people”, none of whom have ever “been out of England, fought in a war, been in prison, ridden a horse, travelled in an aeroplane, got married, or given birth to a child”. Indeed, while “really vital people… multiply almost as automatically as animals”, the Comstocks have “lost all impulse to reproduce themselves”. Their clan has dwindled, between generations, from twelve to eleven to two, Gordon and his sister, both childless, and there seems “no reason why they should not continue in the same style until they died. Year in, year out, nothing ever happened in the Comstock family.”

His relationship with Rosemary is no less difficult. The night they at last plan together, after two years, is a disappointing failure, sexually and emotionally. When they get back together, at the end, their prospects are still very bad.

But they are shared. Before Gordon needed “to retail his troubles to somebody” and if he still has those troubles, he also has that somebody. He and Rosemary are essentially fond of each other, kind to each other, and happy in each other’s company:

Gordon and Rosemary never grew tired of this kind of thing. Each laughed with delight at the other’s absurdities. There was a merry war between them. Even as they disputed, arm in arm, they pressed their bodies delightedly together. They were very happy. Indeed, they adored one another. Each was to the other a standing joke and an object infinitely precious.

After they marry, they can afford only another nasty flat. But marriage, if bad, is still desirable. Gordon has “pined for the difficulty of it, the reality, the pain.” Once that pain is his he feels relief that “he could get back to decent, fully human life.” He is reconciled to life as it is. “Somebody or other had said that the modern world is only habitable by saints and scoundrels. He, Gordon, wasn’t a saint. Better, then, to be an unpretending scoundrel along with the others. It was what he had secretly pined for; now that he had acknowledged his desire and surrendered to it, he was at peace.”

There are certainly notes of the Gandhi essay there, in them finding happiness by rejecting sainthood. And sure enough, the cheap jolly dinner they and Gordon’s one friend share after their registry office marriage is emphatically flavourful: “garlic sausage with bread and butter, fried plaice, entrecôte aux pommes frites, and a rather watery caramel pudding”.

After it they go to their flat. They run up the stairs. It seems “a tremendous adventure to have this place of their own”. The book closes as Rosemary feels something in her belly. “Well, once again things were happening in the Comstock family.” They join the masses who “with their children and their scraps of furniture and their aspidistras… contrived to keep their decency. … ‘kept themselves respectable’—kept the aspidistra flying. Besides, they were alive. They were bound up in the bundle of life. They begot children, which is what the saints and the soul-savers never by any chance do.”

If the choice is between a story like that and becoming a saint or soul-saver, that choice is an easy one by the end of Aspidistra:

Her arms still round him, she leaned a little backwards, pressing her belly against his with a sort of innocent voluptuousness.

‘Life is worth living, isn’t it, Gordon?’

‘Sometimes.’

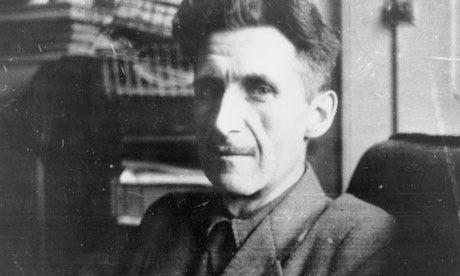

One night in August I reeled from a pub and found myself coming to Orwell’s statue outside Broadcasting House. Because I was coming from the side, and the statue is black, I did not recognise it immediately. But I had an idea, since it’s very large and of distinct shape. So the period between knowing it might be him and being sure was long. During it a very intense hope that it would be him bloomed, and when I was sure and looking up at him I felt very moved. I think I had forgotten how much he meant to me. Here is how it looked:

Here are my recs, in descending order:

Keep the Aspidistra Flying

Essays

Animal Farm

Down and Out in Paris and London

1984

A Clergyman’s Daughter

Hope you liked that. Sorry it was quite long. Next week, PL’s thirtieth, is a very special edition! I hope your week is full of “the pain of living”.

GM

Ghandi,before he decided, in later life,to become a saint led a very colourful life. Much the same can be said for one our home grown ones,Malcolm Muggeridge who also took the same ascetic path as he grew old.

The moral seems to be that if you must start on the path to sainthood then the later you start the better.

In the words of that wisest of saints, Augustine: ''Lord make me chaste but not yet''.

On the subject of Orwell I think that another of his works that is required reading is: ''Homage to Catalonia''. It is the key to understanding the direction his later works took.

Thank you. Enjoyed this. Read most of your list far too long ago - but it’s the essays that keep pulling me back. I don’t know The Clergyman’s Daughter, so must have a look at that. Congratulations on hitting 100!