The first wickedly combustible rant in a Dostoevsky, the first stunning emotional depth charge in an Eliot, the first splash of linguistic largesse in a Fitzgerald. Returning to loved authors, there is often some moment that tells you you are back in the right world.

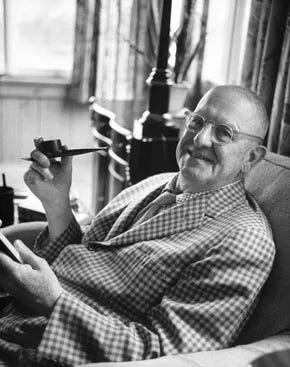

And there are few authors more dearly treasured than Pelham Grenville Wodehouse. It is hard to picture volumes produced more lovingly than Everyman’s Wodehouse collection, which was published in 2000 and filled tables on a recent Tuesday night in the jolly barroom of Wilton’s Music Hall in east London. The event was ‘Plum: Homage to Happiness’, a three-hour appreciation hosted by Stephen Fry. The vague occasion, fifty years since the writer’s death, was missed by three months, more than anything an excuse for a “beano”.

The signature, recognisable moment in Wodehouse’s best and most famous stories – those of hapless Bertram Wooster and his canny manservant Reginald Jeeves – comes when the stakes are set. The first chapter of the pair’s first novel is titled ‘Jeeves Gives Notice’, and give notice he must. For Bertie to end up “in the soup”, he must be without Jeeves, so the bond must be sundered by some disagreement. Since the full drama of the stories depends on these catalytic estrangements, you might expect them to be pretty, well, dramatic.

Instead, Jeeves quits in that book (Thank You, Jeeves) because Bertie will not stop playing his new banjolele, “an instrument to which I had become greatly addicted of late.” Elsewhere they part over Bertie’s enthusiasm for purple cummerbunds (The Inimitable Jeeves) or brass-buttoned mess jackets (Right Ho, Jeeves). You ask if that’s really it. If this cloud is to disburse the plot’s full measure of Storm Und Drang, we expect it had better store up some pretty heavy weather, and it looks a touch light from here. But as the book cruises gently on, in its reliable low gear, you are the assured soothingly that yes, that’s it. That’s as bad as things will get. All that remains now is for Bertie’s hatched scheme to goes hilariously wrong, but only in a way the reader has seen coming, and then for Jeeves to rescue him, but only in a way that surprises you with how many happy endings can arrive at once.

On the inside flap of the Everyman collection, Evelyn Waugh is quoted: “Wodehouse’s idyllic world can never stale. He will continue to release future generations from captivity that may be more irksome than our own.” Stephen Fry has called the work “simply bliss. There's no other word for it. You are bathed in a bath of bliss.”

Wodehouse is broadly held now as the England’s greatest comic writer. But there is an odd shade to the esteem. Idylls and bliss are not quite words you would use for Doestoevsky and co. They get graver words. “Bliss” contains a chance of naivety. And to be “blissed out” is to have gone too far away from reality. People reach, discussing Wodehouse, for Genesis. His world is “heavenly” and “Edenic”. It may be truer to say “prelapsarian”. But it might be truer yet to say “pre-war”.

Opinion against Wodehouse was formed when he started publishing and mounted as Europe progressed from Ferdinand’s grave to Hitler’s. Wodehouse could have nothing useful to tell the age, Virginia Woolf declared human character had changed, Wodehouse was stranded in what his critics were not yet calling the long nineteenth century. They hissed “Edwardian!” As Wodehouse knew, his was “always a small world”, untouched by danger or grief. Purple cummerbunds don’t match service jackets.

Some might point out that Wodehouse dined with Churchill, and that the great war’s great shepherd endeavoured to keep his humour all through the darkest hour. Others, though, might doubt the record of the Wodehousian-Churchillian leader in Downing Street at the next world crisis. But either way, there is enough in Wodehouse’s life to find him guilty of innocence.

A case of mumps in his youth seems to have left him sexless for life. He adopted his wife’s children, and never had any himself. George Orwell called the absence of sex in the stories an “enormous sacrifice for a farcical writer to make”, but it was a costless one: there was nothing to repress. While such docility might keep you from trouble, however, it won’t keep trouble from you. Childlike wonder is well and good until everything starts getting fucked.

Wodehouse was writing at his French villa as German forces advanced through Belgium in the summer of 1940, and he was captured apparently without apprehending his peril. He consented, during a mild internment, to do some ‘non-political’ media work for the Germans, including radio broadcasts and an article. He said was “just as I’m about to feel belligerent about some country I meet a decent sort of chap.” There was uproar in the UK. The BBC carried a Daily Mirror column accusing him of aiding Nazi propaganda. Demands that he be tried as a traitor continued for years.

It may be only that his prestige recovered to its current heights after the war because his actions were excused or that the memory of them just faded with those of the war. But it may have been something else. Reflecting on how the big wars had affected Europe, the critic George Steiner felt that the 70 million deaths between 1914 and 1947 had ruined not comedy, but tragedy. “The political inhumanity of our time, moreover, has demeaned and brutalized language beyond any precedent,” he wrote, and “thus we grow insensible to fresh outrage.” Numb to the tragic style, it might be logical that we would turn to the least tragic of all. If we can express nothing, it might be natural that we look to laughter, which expresses itself.

Or it may be simple. The first reason to love anything, after all, is that you enjoy its company. Wodehouse felt his characters “seem[ed] creatures of a dead past” because they were “friends of all the world… warming the hearts of all.” And there are few heartier laughs to be had than the chaotic dissolution of Bertie’s plan to push the kid Oswald into a river so that Young Bingo can rescue him and thereby impress Honoria Glossop. Wodehouse’s stories are careful creations, flawlessly told. If they are virgin births, they are immaculate conceptions too

.

I am pleased to say that this week’s fantastic New Statesman Weekend Essay is my first commissioned and edited piece. Mike Jay wrote on ketamine and how we all ended up in a Great British K-Hole.

Keep an eye out, by the way, for me on the NS site this week and for the magazine in the newsstand on Friday: it will be an immense issue.

Lastly, please say hi if you are going this week to any of Substack’s London party, Dominic Cummings’s Oxford talk, Thom Yorke’s Hamlet in Stratford-Upon-Avon, the Soho Reading series, or this next Friday.

Thanks for your continued support everyone and I hope you have great weekends :)

GM

Nice piece, and what a lovely warm bath Wodehouse always is to climb back into. There's a fascinating back story to his wartime scrape and the weird national character assassination on the BBC. I wrote about it here https://paulgeorge.substack.com/p/cancelled. Take a look if you have a few minutes.

There’s a PG Wodehouse Everyman Library Subscription for £12.99/month and in only eight years and 1 month you could own the complete collection.